The Raystown Lake Region boasts some of the nation’s most significant contributions to America’s Industrial Revolution. The rich history of the resources - and people - here are well-curated and on display at tourist destinations like the East Broad Top Railroad, Broad Top Area Coal Miners Museum and Friends of the East Broad Top Museum, offering visitors an immersive glimpse into what life was like for families in the 19th and early 20th centuries. One of the industries woven deeply into the fabric of this region is coal mining, which was “king” in Southern Huntingdon County for many years.

A Coal Miner’s Life

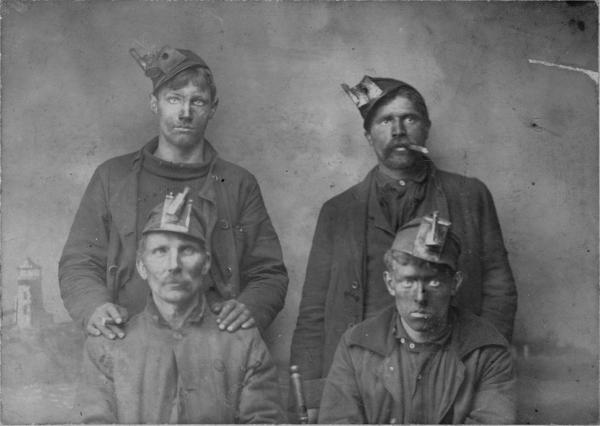

A coal miner’s day in Robertsdale, Pa., during the 19th century was long, grueling, and fraught with dangers compared to today’s work standards. Part of the broader Broad Top Region of Huntingdon County, Robertsdale - once referred to as simply Roberts - is a tiny rural town that was a major hub for coal mining. The mines in this area were developed after the discovery of rich coal seams in the early 1800s, which attracted an influx of workers. These miners, many of whom were immigrants from Europe, labored in difficult conditions, often enduring long hours in poorly ventilated, hazardous mines.

Sunrise in Coal Country

A coal miner’s work day typically began long before sunrise. A coal miner, let’s call him “Henry,” a man in his 30s, might wake up around 4 or 5 a.m. in a modest, small cabin or a company-owned house shared with his wife and children. The winter mornings in the dark mountain hollows in Pennsylvania can be especially cold, leaving frost on single-paned windows and a biting chill in the air. There was no running water in rural homes at that time, and heat came from a stove that burned coal or wood.

Henry would dress in heavy woolen clothes - thick pants, a shirt, a vest and a jacket. His leather boots were likely worn but still sturdy enough for the harsh terrain. He might wrap a cloth around his neck to protect it from the wind and coal dust, and if the day was particularly cold, a wool cap would add warmth.

Walking to Work

Around 5:30 a.m., a bell or whistle from the coal company’s headquarters would ring through the town, signaling it was time for the men to gather at the mine entrance. Many would walk to work, the sound of their footsteps mingling with the occasional cough or tobacco spit.

coal company’s headquarters would ring through the town, signaling it was time for the men to gather at the mine entrance. Many would walk to work, the sound of their footsteps mingling with the occasional cough or tobacco spit.

As they neared the mine, the men would meet up with fellow miners with whom they shared long hours, hard work and a sense of community. There were a few women too, who helped out by washing clothes or delivering food to the men.

At the mine entrance, miners would be lined up and counted by a foreman or other supervisory staff. The foreman would give basic instructions or warnings before allowing the men to enter the work area.

Inside the Mine

The mine entrance was a narrow, low-ceilinged tunnel framed by wood beams. (Visitors to the Friends of the East Broad Top Museum can catch a glimpse of a mine entrance while on a walking tour.) A few oil lamps might have lit the way as the men moved further into the mine shaft. The air was cold and damp at first, but as they descended deeper, it became increasingly hot and stifling. Coal dust filled the air constantly, and it was nearly impossible to avoid inhaling it. Over time, this dust could lead to respiratory problems like black lung disease, a chronic illness common among miners of that era.

For miners like Henry, the workday often began with digging through rock to reach the coal veins. The men used picks, shovels and hammers to break apart the rock and extract the coal. In the deeper parts of the mine, the tunnels could become more narrow and poorly supported. Wooden beams were often used to shore up the walls, but falling rock was a constant threat.

The deeper the miners went, the more dangerous conditions might become. The tunnels were sometimes only three or four feet high, forcing miners to stoop or crawl for long stretches. The air was thick with coal dust and sometimes dangerous methane gas, which could cause explosions if ignited.

Hard Work

Depending on the miner’s task, his work might involve picking coal out of the rock, shoveling it into carts, or hauling the filled carts up to the surface. The men might take a short break mid-morning, but there was typically no formal lunch hour. A miner’s meal might be something like bread, hard-boiled eggs or salted meat.

The risks of cave-ins, gas explosions and other  hazards were constant. Many miners died young due to these accidents, and for those who survived, long-term health issues like lung diseases were common. At the time, the mine owners often didn’t provide adequate safety measures or compensation for miners’ injuries or deaths. A cave-in could bury men alive or injure them beyond repair, while methane gas could cause explosions that would take entire shifts of miners with it.

hazards were constant. Many miners died young due to these accidents, and for those who survived, long-term health issues like lung diseases were common. At the time, the mine owners often didn’t provide adequate safety measures or compensation for miners’ injuries or deaths. A cave-in could bury men alive or injure them beyond repair, while methane gas could cause explosions that would take entire shifts of miners with it.

Miners knew the dangers, and the pay was meager, but the need to feed themselves and their families kept them coming back to the mine each day.

At around 3:30 or 4 p.m., the workday would wrap up. The whistle would blow, signaling the end of the shift. The end of the day was likely a relief, though the miners’ bodies were exhausted from hours of lifting, bending and working in cramped conditions. As the miners walked back to their homes, they were covered in soot and coal dust, their faces grimy and their muscles aching.

Evenings at Home

Upon arriving home, miners would shed their dirty clothes, and their wives might prepare a simple meal, which could include potatoes, vegetables or leftover meat from the previous night.

Though the days were long, family life was central to the community in the Broad Top area. After supper, the miners would spend time with their children, who played around the small cabins or did chores to help with the household. The evenings were quiet - miners likely didn’t have much energy for anything else. They would go to bed early, knowing that another day in the mine awaited them.

Necessary to Survive

This was the cycle of life for a coal miner in Robertsdale in the 1800s: long days of hard labor, dark and often dangerous working conditions, and an ever-present threat of injury or death. The pay was low, but the work was necessary to sustain families.

The average life expectancy of a coal miner was significantly lower than the general population at that time, with estimates placing it around 40-50 years old due to the harsh working conditions, high risk of accidents and prevalent lung diseases.

Despite the hardships, the coal mining community of Robertsdale persevered, forming a tight-knit, resilient group of workers who relied on each other to endure the harsh conditions and make a living from the coal that fueled the growing nation.